“What the Medellín cartel did is exactly what any global pharmaceutical firm has to do,” says Philip Heymann, a Harvard Law School professor who fought the drug cartels as a deputy U.S.

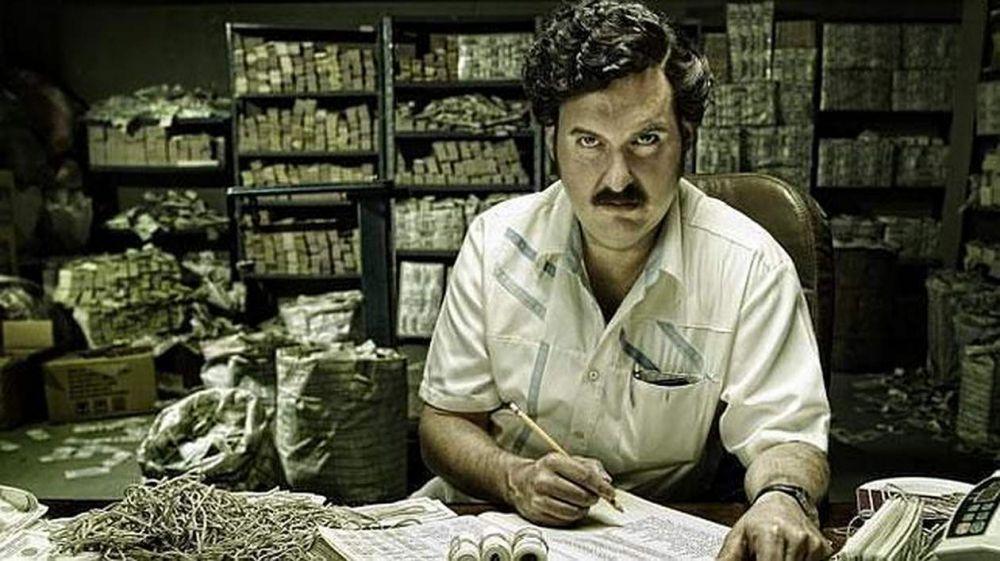

It was not only a lethal purveyor of stimulants and mayhem, it was also a brilliant business, no different in many ways from a Fortune 500 corporation, but built to operate wholly outside the law. Pablo Escobar and his partners called their business a cartel, but instead of controlling price and supply, it behaved far more like a criminal syndicate that pumped an endless supply of cocaine into the market and let the market set the price. At its height, it earned as much as $4 billion a year-most of it cash-for its members and controlled 80 percent of the cocaine supply in the United States, leaving tens of thousands of corpses in its wake.

This focus helped me avoid reproducing what historian Luis Astorga calls “ the mythology of the narcotrafficker.” There are no Pablo Escobars in my book – just everyday Colombians who seized on their country’s growing commercial ties to the world’s largest drug market – the United States – to launch a global business.The Medellín Cartel was an empire of stunning sweep and unimaginable violence.

I also kept my questions focused on the defunct marijuana business – not the active cocaine trade. To stay safe while studying an industry that uses cash and violence to keep its affairs clandestine, I relied on friends and family, who helped me establish contacts and identify information sources. But armed groups, including cartels, still operate there. I began collecting testimonials in northern Colombia in the early 2000s, during Colombia’s 52-year armed conflict. Some of my research was archival, conducted in Colombia and the U.S. My father is from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta area, where marijuana once boomed. This began as a personal quest to understand the country of my childhood. We just don’t know how cocaine simultaneously supplanted marijuana as the staple drug crop of the peasant economy up north. In southern Colombia, academics have documented how Pablo Escobar’s generation of traffickers financed new settlers to grow coca leaf, the base ingredient in cocaine, in the 1980s. But it doesn’t detail their next transition, from marijuana to cocaine. My book recounts how and why people in northern Colombia used their farming experience to grow and export marijuana. Timothy Ross/Hulton Archive/Getty Images What still isn’t known Police search suspected marijuana growers in the Guajira, Colombia, 1980. People who’d grown legal commodity crops saw opportunity in exporting an illegal one to the United States: marijuana. These changes made some rural Colombians rich but, my research shows, impoverished peasant farmers in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. By the 1970s, Colombia was expanding international trade, particularly with the U.S. Throughout the 20th century, Colombia worked to build its banana export sector, create a cotton belt to supply Colombian textile factories and to redistribute land. I find Colombia’s marijuana boom was actually an unintended consequence of state-led efforts to economically develop Colombia. My research also disproves the long-held academic consensus that illegal drug markets emerge in remote areas where the state has insufficient presence.

Traffickers retaliated, giving rise to the now familiar “war on drugs”-style dynamic of escalating conflict. governments in 1978 launched a militarized campaign to eradicate marijuana crops and increase drug interdictions. This research upends other old tropes about the drug trade, including the idea that it’s inherently violent.Ĭolombia’s marijuana economy operated relatively peacefully until the Colombian and U.S.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)